Sand is considered to be an essential ingredient/material when it comes to building civilisations. As global urbanisation continues, the demand for sand for making concrete, building sites, filling roads, making bricks, making glass, sandpapers, etc. As the global population continues to rise and so does the expansion of cities, demand for sand is only expected to grow.

Fig.1: Demand for sand

Source: United Nations Environment Programme1

Every year, billion tons of sand is extracted from lakes, riverbeds, coastlines, and deltas, which makes sand the planet’s most mined mineral. However, the process by which sand can be naturally replenished is extremely slow. Excessive extraction of sand has earned a huge disrepute and has become a huge cause of concern for ecology.

Sand mining refers to the process of extraction of sand usually from an open pit. It is an activity in which sand is removed from the rivers, streams, and lakes. Beaches all over the world are being mined for sand for a variety of uses. Sand mining has tripled in the last two decades because of the increase in demand as reported by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP).

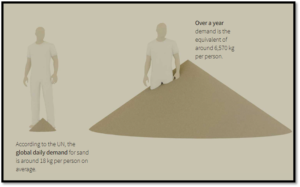

III-effects of sand mining

Sand is essential for the maintenance of rivers. Indiscriminate and excessive mining of sand has recorded various ill-effects inasmuch as:

-

Excessive mining of sand affects the regular course of the river. A change in the course of a river causes river erosion which further leads to floods during monsoon.

-

Serious effects on the nearby wildlife which is dependent on the sandy banks for their survival.

-

Intrusion with the sand on the riverbed causes disturbance in the water, which is injurious to sea animals resulting in hindrances/difficulties to the population which relies on fishing for their livelihoods.

-

Removing coastal barriers leads to the exposure of beachside areas to floods, cyclones, and tsunamis.

-

Depletion of sand in the riverbed resulting in the deepening of riverbeds and the widening of river mouths which increases the salinity of the water.

-

Riverbed becomes dry due to exposure to solar radiations.

-

Sand mining affects the homes and livelihoods of people living nearby.

-

Sand mining also destructs picturesque beaches.

-

Sand mining converts the riverbeds into large and deep pits which results in a fall in the groundwater index.

-

Sand mining has a straight impact on the physical characteristics of the stream, such as channel geometry, bed elevation, substratum composition, stability, flow velocity.

The impact of sand mining on environment could be summed up by the following figure:

Fig. 2: The impact of sand mining on environment

Source: Science of the Total Environment2

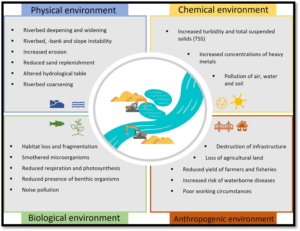

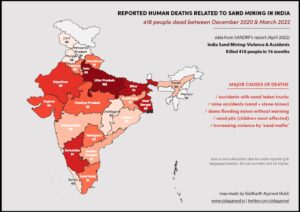

Besides the loss to habitat, illegal sand mining also causes violence. Villagers, media reporters, environment activists and government officers are brutally harmed and killed year after year when they raise objections to or take any action against illegal sand mining. In addition to rampant killings, there have been several instances where open threats were given to villagers, government officials, activists, and reporters. A study reflects that around 418 people died and 438 people got injured in India from December 2020 to March 2022 in sand mining cases. The highest number of deaths have been reported in North India (95), followed by 42 in West and Central India, 41 in East India and 15 in South India.3

The causes of death are drowning in deep sand mining pits, the downfall of sand mounds, and the caving in of sand mines. Vehicles that are involved in sand mining business are often reported to be damaged by road accidents.

Fig. 3: Sand mining violence and accidents from December 2020 to March 2022

Source: SANDRP’s Report, April 2022

Fig. 4: Statewise death toll due to sand mining related activities in India from December 2020 to March 2022

Source: SANDRP’s Report, April 2022

Workers operating in sand mines or stone quarries have an alarming exposure to several health hazards that can also become life threatening. They work without any proper safety gear and survive on meagre compensation. They mostly come from economically and socially weaker sections or tribal communities.

Excessive mining also leads to pits in riverbeds. These pits act as death traps that can lure children who are unmindful of the depth. Children visit riverbanks for playing or bathing or just for leisure and they slip inside these deep pits which ultimately leads to their death on the spot.

Sand mining in India

In India, rather than treating sand as a valuable natural source, it is often treated like a commodity. Sand mining in India has been making news mostly for notorious reasons. It has caused irreversible damage to the environment and virtually killed many of our rivers. Sand mining has led to the devastation of rivers like Narmada, Chambal, and Betwa in Madhya Pradesh. Similarly, in Kerala, Bharathappuzha River has fallen victim to sand mining. Gujarat, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu have also reported about the negative impact that is the result of sand mining across their rivers.4 The expansion of real estate and infrastructure industries has fuelled the need for excessive sand mining. indiscriminate sand mining against the laws of nature has become a serious threat to our environment. There has been a constant temptation on the part of unscrupulous persons to extract more and more quantity of sand while discarding regulations and environmental concerns. The lack of proper monitoring technology for river sand mining has led to widespread illegal mining.

A report on ABC Foreign Correspondents states that “… the sand mining business in India offers employment to over 35 million people and it is valued at over $126 billion per annum. In the year 2015-2016, there were over 19,000 cases of illegal minor minerals including sand in the country….”

Legal regime in India

MMDR Act, 1957

Sand has been notified as a “minor mineral” under Section 3(e) of the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act of 195755 (hereinafter referred to as “the MMDR Act”). The term “ordinary sand” that is used in clause (e) of Section 3 of the MMDR Act, 1957 has been given a clear understanding through Rule 70 of the Mineral Concession Rules, 196066 as follows:

70. Sand not be treated as minor mineral when used for certain purposes. — Sand shall not be treated as a minor mineral when used for any of the following purpose, namely:

(i) purposes of refractory and manufacture of ceramic;

(ii) metallurgical purposes;

(iii) optical purposes;

(iv) purposes of stowing in coal mines;

(v) for manufacture of silvicrete cement;

(vi) for manufacture of sodium silicate; and

(vii) for manufacture of pottery and glass.

Section 15 of the MMDR Act states that “the State Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette make rules for regulating the grant of quarry leases, mining leases or other mineral concessions in respect of minor minerals and for purposes connected therewith”.7 Further, Section 23-C of the MMDR Act states that:

“The State Governments may, by notification in the Official Gazette, make rules for preventing illegal mining, transportation and storage of minerals and for the purposes connected therewith.”8

Acting in accordance with the provisions of Section 23-C of the Act, 21 State Governments, namely, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Goa, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Nagaland, Odisha, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and West Bengal have brought forward rules to control the menace of illegal mining. 22 State Governments have set up task forces at State and district levels to curb illegal mining and assess the action taken by departments for checking the illegal mining activities at State and district levels.9

Section 4 of the Act specifically states that mining without necessary permits is illegal. This includes sand mining also.10

An amendment was brought forward in 2015 to the MMDR Act, 1957.11 The amendment was enforced on 12-1-2015. The Amendment Act has increased punishment for illegal mining that now exceeds to imprisonment for up to five years and fine that may extend to five lakh rupees per hectare of the area.12 Provisions have also been included in the Act to set up Special Courts that help in providing speedy trial of offences relating to illegal mining.

Under this Act, a statutory obligation is cast upon the State Governments to enact laws and adopt rules that govern mining activities; there is a lack of consistency from State to State. Many States have framed different regulations in respect of minor minerals which give rise to inconsistencies and chaos.

Environment Protection Act, 1986

Environment Impact Assessment Notification, 2006 was issued by the Central Government under the provisions of the Environment Protection Act, 1986.13 As per the notification, “the mining of minerals with a lease area of five or more hectares would require prior environmental clearance”.14 The notification however does not clearly point out any difference between the major or minor minerals.

Natural resources belong to the public, and they are an asset to the nation as a whole. The doctrine of public trust extends to natural resources also and it rests on the important principle that certain resources like air, sea, water, and forests are of great importance to the public. Mining of sand from the riverbeds without licence or permit thus constitutes an offence of theft of minerals under Sections 378 and 379 of the Penal Code, 1860 as natural resources are also the property of the public, and the State is its trustee.15

In 2016, the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has recently issued Sustainable Sand Mining Management Guidelines, 2016.16 Apart from laying importance on sustainability in sand mining and monitoring of sand mining activities, the guidelines also focus on the conservation, protection and restoration of ecological systems while maintaining river equilibrium. The salient features of the guidelines are as follows:

-

It is aimed to ensure that sand and gravel mining is done in an environmentally sustainable and socially responsible manner.

-

Implementing safeguards for checking illegal and indiscriminate mining.

-

Monitoring system for sustainable sand mining.

-

To improve the effectiveness of monitoring of mining and transportation of mined-out material.

-

Its object is to ensure the conservation of the river equilibrium and its natural environment by protection and restoration of the ecological system.

-

To ensure the rivers are protected from bank and bed erosion beyond their stable profile.

-

Streamlining and simplifying the process for grant of environmental clearance (EC) for sustainable mining.

-

Prevent groundwater pollution by prohibiting sand mining on fissures where it works as a filter prior to groundwater recharge.

-

Streamlining and simplifying the process for grant of environmental clearance for sustainable mining.

In the recent past, there has been an upsurge in the number of illegal mining cases. Illegal mining constitutes loss of revenue to the State, and degradation of the environment apart from causing annoyance and law and order situations. Adhering to the need to monitor mining activities, particularly sand mining, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has brought forward the Enforcement and Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining, 2020.17

The main objective of these Guidelines is to regulate sand mining in the country and to control the instance of illegal mining. The salient features of the guidelines are as follows:

-

Effective monitoring of sand mining from the identification of sand mineral sources to its dispatch and end use by consumers and the general public and look at a uniform protocol for the whole country.

-

Constant monitoring of mining activity is to be done by drones and night surveillance.

-

Auditing of rivers by the State.

-

Dedicated task forces at district levels should be set up by the States which shall prepare district survey reports.

-

Conducting a replenishment study for the riverbed by the State to minimise the adverse impacts arising due to excessive sand extraction.

-

Prohibition of riverbed mining during monsoon seasons.

Other than these guidelines and statutes at the Central level, each State has also implemented their own policies and legislations in consonance with the MMDR Act, 1957, and the Guidelines of 2016 and 2020.

Of late the issues relating to sand mining has also engaged attention of higher judiciary and National Green Tribunal (NGT). Over the recent past, the courts particularly the Supreme Court and NGT has dealt the cases of illegal extraction sand with heavy hands. The courts have tried to address the lacuna, loopholes, and tendency of vested interests to evade the rigour of law in the following cases:

In A. Chidambaram v. District Collector18, the High Court of Madras held that:

“… the Tamil Nadu Government to ban the removal or extraction of sand from rivers where the present sand bed level is below the required level as fixed by the State because such activities were causing environmental degradation in that area….”

Similarly, in Paristhithi Samrakshana Sangham v. State of Kerala19, the High Court of Kerala held that:

… when the Government is presented with a choice between irreparable injury to the environment and severe damage to economic interests, protection of the environment would have precedence. No permit shall be given to any person for sand mining in the area concerned unless a sand audit is conducted.”

The courts through their decisions from time to time have been encouraging the Government on the Centre as well as the State level to impose conditions on sand mining activities in India. The High Court of Kerala in Soman v. Geologist20 held:

… the principle of sustainable development is now a part of environmental jurisprudence, flowing from Article 21 of the Constitution of India, and hence the State is bound to impose any conditions while granting the permit for sand mining.…

The Supreme Court in Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana21 heard challenges to auction notices issued by the Department of Mines and Geology, Government of Haryana which invites bidders to participate in the auction for extraction of minor minerals not exceeding 4.5 hectares in each case. The notices were challenged to be violative of the Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, 2006 which specifies that the authority concerned requires prior environmental clearance before granting of mining leases of area equal to or more than 5 hectares. In the auction notices by Haryana Government, an attempt was made to defy the EIA Notification by dividing the land into pieces and reducing the area of each piece to less than 5 hectares. Taking note of the matter, the Court ordered Central Empowered Committee (CEC) to make a local inspection with respect to alleged illegal mining in U.P., Rajasthan, and Haryana and also whether there is an attempt to defy the EIA Notification of 2006 by breaking the area into pieces of less than 5 hectares to escape the required environmental impact assessment. The CEC submitted a detailed report on the matter, but the report was silent on the issue of illegal mining and its impact on the environment and whether the said notices were an attempt to flout the notification of EIA. The Court observed that minor minerals were brought under the sphere of the EIA Notification of 2006. The MoEF noticed that the collective impact of mining of minor minerals was not taken into consideration. The MoEF constituted a core group wherein the Secretary (Environment and Forests) was the Chairman. The core group was constituted to look into the collective environmental aspects that are associated with the mining of minor minerals. The objectives of the core group were as under:

-

To take into consideration the collective impact of mining of minor minerals on the environment.

-

To bring forward safeguards that are required to control the adverse impacts of mining.

-

Lay down model guidelines that can address the pressing issue of mining as well as environmental concerns.

The following recommendations were then given by the MoEF:

-

Definition of minerals should be re-examined into major and minor categories.

-

There should be uniformity in the extent of the area to be granted for the mine lease and the time period of the lease. It was recommended that the minimum size of the mine lease should be 5 hectares and the minimum period of the mine lease should be 5 years.

-

It may be desirable to adopt a cluster approach in case of smaller mine leases.

-

Provision for preparation and approval of mine plan in the case of major minerals may appropriately be provided in the rules governing the mining of minor minerals by the respective State Governments.

-

There is a need to create a separate corpus which may be utilised for reclamation and rehabilitation of mined out areas.

-

Detailed hydrogeological report should be prepared in respect of any mining operation for minor minerals.

-

Model mineral concession rules may be framed for minor minerals as well and the minor minerals may be subjected to a simpler regulatory regime.

The States/Union Territories were directed through this judgment22 to give due weight to the recommendations given by MoEF which are made after due consultation with the State Governments as well as Union Territories. Further it was directed that on the lines of EIA Notification of 2006, even the leases of minor minerals including their renewal for an area of less than 5 hectares be granted by the States/UTs only after getting prior environmental clearance from MoEF.

In Anjani Kumar v. State of U.P.23, the following directions were passed by the NGT with respect to sand mining:

-

Obtaining environmental clearance shall be a condition precedent to carrying on of the mining activity or execution of the lease.

-

The State Government and all its agencies and instrumentalities would ensure that the protection and replenishment of natural resources including sand is duly provided for in the mining lease.

-

The State Government and its instrumentalities shall also ensure that the terms and conditions of the mining lease would contain all the relevant clauses to carry out sustainable mining.

The National Green Tribunal, expressed its deep concern with regard to illegal sand mining in Anumolu Gandhi v. State of A.P.24 The Tribunal has held that:

… it is the duty of the Government to provide complete protection to the natural resources as a trustee of the public at large. All unregulated sand mining that is being conducted without following the prescribed procedure in the State of Andhra Pradesh should be prohibited….

In State of Bihar v. Pawan Kumar25, the three-Judge Bench of the Supreme Court observed that:

“… a total ban on legal mining of sand, apart from giving rise to illegal mining, will also cause huge loss to the public exchequer. The following directions are thereby issued:

1. The District Survey Reports for the purpose of mining in the State of Bihar shall be undertaken afresh.

2. The reports shall be prepared by undertaking site visits and also by using modern technology.

3. The draft reports shall be examined by the State Expert Appraisal Committee which shall consider the grant of approval.

4. A strict adherence to the procedure and parameters laid down in the policy laid down in 2020 i.e. Enforcement and Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining.”

The Supreme Court in Bajri Lease Lol Holders Welfare Society v. State of Rajasthan26 held that:

“… unabated illegal mining has resulted in the emergence of the sand mafia who conduct illegal mining in the manner of organised criminal activities and have been involved in brutal attacks against members of local communities, enforcement officials, reporters and social activists who dare object to unlawful sand excavation. Section 21(5) of the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957 empowers the State Government to recover the price of the illegally mined mineral, in addition to recovery of rent, royalty or tax, that the penalty recommended by the Central Empowered Committee for illegal sand mining would be in addition to the penalty that can be imposed by the State Government in terms of Section 21(5) of the Act. The report also mentioned that the compensation/penalty/value of sand needs to be recovered in respect of illegal sand mining as below:

(a) compensation for environmental damage;

(b) value of the vehicles to be realised before release;

(c) recovery of value of the illegally mined sand; and

(d) the above compensation will be over and above any penalty imposed as per existing rules or provisions.”

Illegal mining

The Supreme Court in the judgment given in Common Cause v. Union of India27 as:

mining operations undertaken by any person in any area without holding a mining lease and any other mining operation conducted in violation of the terms of the mining scheme, the mining plan, and the mining lease as well as the statutes such as the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, the Forest (Conservation) Act, 198028, the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 197429, and the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 198130 and the Wild Life Protection Act, 197231.

Even after several suggestions by the courts as well as tribunal, the States have not come up with an effective mechanism to keep a check on illegal sand mining. On the contrary, some of the State Governments have found out ways to mould the legal mandates under the influence of pressure groups.

Compensation in cases of illegal sand mining

There is no law or mechanism by which compensation can be extracted from the miners to remedy the loss done by illegal mining.

Compensation for illegal mining is to be subjected to Sections 21(1) and (5) of the MMDR Act, 1957. Section 21(1) imposes a penalty for contravention of the provisions of sub-section (1) or sub-section (1-A) of Section 4 which requires due compliance with the terms and conditions laid down in reconnaissance permit, or a prospecting licence or a mining lease. Section 21(5) imposes a penalty on any person who without any lawful authority extracts any mineral from any land.

The topic of compensation for illegal mining was untouched till the decision of the NGT (Principal Bench), New Delhi by order dated 5-4-2019 in National Green Tribunal Bar Association v. Virender Singh (State of Gujarat)32, a case related to illegal sand mining from riverbeds in different States, constituted a committee which comprised of representatives of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India (MoEF&CC), Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), Indian Institute of Forest Management, Bhopal (IIFM), Institute of Economic Growth, New Delhi (IEG) and Madras School of Economics (MSE). The Committee was constituted with an objective to:

57. … prepare a scale of compensation, after including the components mentioned in the order, which can be adopted in the whole of country…. The nodal agency for compliance and contribution is CPCB. The Committee may also take professional service of an expert/institution in the matter if it so desires.33

In view of this order of the NGT, the Committee prepared a report to suggest a scale of compensation to deal with cases of illegal sand mining in the whole of the country.

The Committee suggested that owing to the reality of ongoing economic activities causing ecological damages implies that the adoption of the polluter pays principle can be a way ahead for raising the resources for undertaking restoration activity to the maximum extent possible. Ideally, the compensation can be determined by making an independent assessment of each river or water body, but till the time such extensive research is being done, the Committee suggested that two approaches can be used to determine compensation. The two approaches are:

-

Direct compensation. ——The compensation under this approach is based on three distinct criteria:

(i) Exceedance factor: The amount of penalty charged should be in proportion to the extent of the illegal extraction of material.

(ii) Risk factor: It reflects the severity of the ecological damages. Risk factor accounts for the extent of severity of damages.

(iii) Deterrence factor: The greater the extent of extraction, the greater the likelihood of cumulative adverse impact. This factor holds the miners accountable in a way that deters them.

-

Net payment value (NPV) approach. ——Total benefits from the activity of sand mining (as represented by the market value of the extracted amount) are deducted from the total ecological costs imposed by the activity.

The above two approaches are interim recommendations for compensation to be charged.

Even after these recommendations of the Committee, the compensation is being charged in their contravention. Recently in Radhamohan Singh v. State of Odisha34, the penalty was imposed arbitrarily as an exorbitant lump sum amount without taking into consideration any parameters that determine the compensation. The approaches recommended by the Committee were interim direction and not to be regarded as binding precedent for each and every future case. It is imperative to point out there should be appropriate law, principles on the basis of which quantum of compensation should be derived.

Sand mining over the world

International and regional frameworks are in place to prevent illegal sand mining, however, despite their existence, they have not been able to prevent this menace. There is a lack of any stringent law on the point and accountability of the wrongdoers. Currently, 200 above international treaties exist that are signed between countries, and their main aim is to restrict and regulate mining activities while keeping in mind environmental concerns. The two most important international treaties that govern sand mining are:

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

Adopted on 10-12-1982, this Convention has been ratified by 162 countries now. It lays down the rules that adhere to the usage of maritime resources. Part XII of the Convention deals with the protection and preservation of marine ecosystems and aquatic wildlife.

Articles 208 and 214 of the Convention impose a duty on the States to create and enforce laws and regulations that help in preventing, reducing, and controlling pollution in the marine environment that has been caused by activities like sand mining.35

Article 194(2) of the Convention directs the State to take necessary steps to ensure that the mining and extraction activities undertaken by them are not carried out in a manner that would result in damage to other States and their environment.36

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

Adopted on 22-5-1992, this Convention was enforced on 29-12-1993 and its aim is to encourage teamwork among countries to defend and protect biodiversity in marine environments while putting in the efforts that are required for the restoration of tarnished ecosystems.

Article 3 of the Convention states that the States could still retain and pursue the right to exploit their resources, but they will be obligated to do so in a responsible manner and ensure that they do not cause any damage to the environment that comes within their jurisdiction, or in the jurisdiction of other States.37

Articles 5, 6 and 7 of the Convention seek cooperation among States to bring forward conservation strategies and programmes for safeguarding sustainable use of natural resources, while on the same hand identifying, monitoring, and restoring those environments which have been drastically damaged as a result of incessant mining.38 Article 7, in particular obligates the member States to identify, monitor and assess the impact of sand mining and other activities on the environment.39

Sand mining in a few countries

|

Basis of Comparison |

China |

US |

UK |

Australia |

|

Condition of sand mining in the prevailing country |

Sand mining is the least regulated, as well as the most corrupt and environmentally damaging in China. |

Demand for sand and gravel has increased to nearly 50 billion metric tons per year. |

Mining in the UK is regulated by planning policies for minerals. |

Australia has the world’s largest mineral sand deposits. |

|

Prevailing law |

The Mineral resources law, 1986 is the national law that governs the prospection of and extraction from mines in China and the registration of mining rights. |

Sand mining was earlier covered under the Mining Law of 1873. However, since 1955, common varieties of sand, gravel, stone, pumice, etc. were removed from the mining law and placed under the Materials Act of 1947. |

Mineral extraction can be done only after receiving an agreement of the landowner and planning permission from the Mineral Planning Authority and any other permits and approvals. |

The Offshore Minerals Act, 1994 regulates mining of minerals offshore i.e. beyond the coastal baseline, in the sea and the seabed. |

|

Restrictions imposed |

Restriction on sand mining activity imposed in March 2021. |

US has substitutes like crushed stone and recycled asphalt for construction-grade sand. |

A team of scientists in the UK have developed a biodegradable construction material made from desert sand. It is as strong as concrete but has half the carbon footprint. |

The Labour State Government of Australia pledged to end sand mining by 2025, but this decision was overturned by the Liberal National Party which succeeded it. |

|

Alternatives |

The suggested alternatives to sand are making construction material from waste material. |

Alternatives to sand that are suggested in Australia are manufactured sand, ore sand and mine waste. |

Way forward

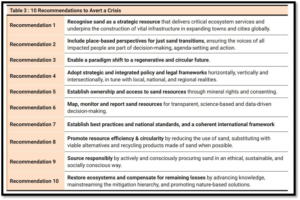

Excess of anything can lead to a disaster, so is the case with sand mining which has caused severe adverse effects. The UNEP has outlined the following recommendations to avert a sand crisis –

Fig. 3: Recommendations to avert sand crisis

Source: UNEP40

Another way to avert the sand crisis would be to bring in alternatives that can easily replace sand and not hinder the development process. Some of the alternatives are:

Manufactured sand

Manufactured sand (hereinafter referred to as the “M-sand”) is a form of manmade sand that is made by crushing hard stones into a fine powder, which is then washed and finely graded. M-sand is widely used as a replacement of ordinary sand for construction purposes. The construction industry is growing on a fast pace which has led to a great increase in the demand for sand. To meet the ever-increasing demand, the sand is being extensively exploited. M-sand does not comprise of any impurities such as clay, dust, and silt coatings. The physical properties of M-sand such as its shape, surface texture, and consistency make it suitable for construction work. Using M-sand for construction purposes has results like increase in durability, more strength, and reduction in segregation, permeability, increased workability, and is economical as a construction material. An added advantage is that M-sand is more eco-friendly than ordinary sand.

However, M-sand also comes with its flaws. It requires more water due to its shape and texture which thereby increases its overall costs. Also, M-sand contains a lot of micro fine particles that affect the strength and workability of concrete.

Copper slag

The extraction of copper metal in refineries results in the production of waste material which is also known as copper slag. Currently, approximately 33 million tonnes of copper slag is generated annually all over the world. India contributes 6-6.5 million tonnes to this total. A publication titled Cement and Concrete Composites and Construction and Building Materials in 200641 gave certain recommendations on the replacement of sand in the construction field. Sand can be replaced by 50 per cent copper slag to obtain concrete that has good strength and durability. A study was undertaken by the Central Road Research Institute (CRRI) which bears proof of the fact that copper slag can become a replacement for sand.

In Singapore, copper slag has been substituted for sand in the production of concrete. The “ready mixed concrete” companies use it. The use of copper slag as a substitute for sand has opened the door to the incorporation of more recycled/waste materials in concrete production.

Granulated blast furnace slag (GBFS)

Granulated blast furnace slag is a waste product that is produced during the processes carried out in the steel industry. This waste product can be upcycled to be used as cement. The working group on cement industry informed that approximately 10 million tonnes of blast furnace slag are currently being produced in India from the iron and steel industry. M.C. Nataraja reported in a study published in the International Journal of Structure and Civil Engineering Research in May 201342, that according to the obtained data, the replacement of sand with granulated blast furnace increases the strength of cement mortar. Use of GBFS in the construction field up to 75 per cent is acceptable.

Bottom ash

Coal combustion leaves behind a material at the bottom of furnaces which is known as bottom ash. It is coarse, granular, and incombustible in nature. India is currently generating around 100 million tonnes of coal ash. Out of this total, approximately 15-20 per cent is bottom ash and the rest constitutes fly ash. The mechanical properties of special concrete that constitutes of 30 per cent replacement of natural sand bottom ash has an optimum usage in concrete that delivers good strength.43

Quarry dust

Quarry dust is a product that occurs as a result of the crushing process which is a concentrated material to be used as aggregates for concrete purposes. Waste material-quarry dust constitutes about 20 to 25 per cent of the total production that is undertaken in each crusher unit. Chandana Sukesh in his study published in the International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering in May 2013 says that:

the ideal percentage of the replacement of sand with the quarry dust is 55 per cent to 75 per cent in case of compressive strength. If combined with fly ash (another industrial waste), 100 per cent replacement of sand can be achieved. The use of fly ash in concrete is desirable because of benefits such as useful disposal of a by-product, increased workability, reduction of cement consumption, increased sulfate resistance, increased resistance to alkali-silica reaction and decreased permeability”.44

Foundry sand

Foundry sand is a by-product of the production of both ferrous and non-ferrous metal casting industries. It is a high-quality silica sand. According to the 42nd Census of World Casting Production of 2007, India comes fourth in terms of total foundry sand production i.e. 7.8 million tonnes. Foundry sand has very high silica content and is regularly disposed of by the metal industry. Presently, there is no mechanism in place for its efficient disposal, but international studies point out that up to 30 per cent foundry sand can be used for the economical and sustainable development of concrete that is used for construction purposes.

Construction and demolition waste

The amount of construction and demolition (C&D) that is generated in India has not been accounted for. The Municipal Corporation of Delhi says it is collecting 4000 tonnes of C&D waste daily from the city which amounts to almost 1.5 million tonnes of waste annually in the city of Delhi alone. Recycled sand aggregate from C&D waste can be used as a replacement to the ordinary sand as it is said to have 10-15 per cent lesser strength than normal concrete and can be safely incorporated in non-structural applications like flooring and filling.

Suggestions and recommendations

The author puts forward the following suggestions for the implementation of sand mining regulations in India:

-

I3MS stands for integrated mines and mineral management system. This portal was developed by Odisha Government to enable the Department of Steel and Mines officials to regulate mining activities through electronic mode. It provides complete details like the name of the lessee, the location of the leased land, the area of the land, and the mineral being extracted. A similar system should be developed for minor minerals like sand to keep a check on sand mining throughout the country. Such a system will provide uniformity in the matters of sand mining.

-

State Government is duty-bound to make regulations regarding sand mining. Some of them have diligently made regulations to govern sand mining in their state. However, some States are still lagging and have not brought forward any regulations to regulate sand mining.

-

Illegal sand mining is all the rage these days. To control this, the vehicles that are used in the sand mining process should be pre-registered on the portal and they should be GPS enabled so that it is easier to keep a track of them. A transit pass may be issued by the authorities to the lessee/contractor/permit holder/mineral dealer for lawful transportation and dispatch of excavated sand.

-

Section 20-A45 of the MMDR Act, 1957 which was incorporated by 2015 Amendment to the Act, gives to the Central Government the power to issue directions to the State Governments, for the efficient conservation of mineral resources, or on any policy matter that affects the national interest, and for the scientific and sustainable development and to prevent exploitation of mineral resources. The Central Government should exercise this power to control the menace of illegal sand mining and bring minimum standards and regulations in sand mining activities.

-

Sand has been wrongly categorised as a minor mineral under Section 3(e) of the MMDR Act, 1957. Sand mining is done on riverbeds and rivers cross several States thus sand mining should not be solely regulated by the State Governments. Sand should be brought under the category of major minerals and the Centre should regulate all operations relating to sand mining. The Centre should frame guidelines that uniformly apply to sand mining in all the States.

-

Section 23-C of the MMDR Act, 1957, gives power to the State Government to make rules for avoiding illegal mining, transportation, and storage of minerals. The State Government should exercise this power to control illegal sand mining and bring in regulations to curb the same.

-

The end consumer who is purchasing sand should be able to produce a bill for the same otherwise the dealing would be termed illegal.

Conclusion

The legal regime presently in place in several States regulates sand as a minor mineral. Stringent provisions are in place that require the mining industry to ensure that their activities are not harmful to the environment. The regulatory authorities keep a check on the effect on the environment of both proposed and existing sand mining projects. The State authorities have the power to close certain areas where sand mining is being conducted, delineate the maximum amount of sand that can be extracted from a particular area and monitor the overall impact that mining has on the environment. Despite such a strong legal framework, the sand mining sector has largely been left unregulated.

The authorities at the State level have failed to enforce laws and it is a common practice by mining authorities to grant mining leases or permission without any regard to environmental factors. Therefore, it is important aspect to regulate sand mining and bring about a law for ousting sand mafias from sand mining.

Quarrying of river sand is an important economic activity as river sand is the most vital raw material for the expansion of infrastructure and the construction industry. However, extreme sand and gravel mining led to the deprivation of rivers. The reduction of sand in the riverbed causes the deepening of rivers which results in the destruction of aquatic life.

It is extremely necessary to have an effective framework that regulates sand mining and considers the environmental issues associated with it. Sand mining leads to a negative impact on biodiversity. It causes loss of aquatic habitat and also destabilises the soil bed structure of riverbanks and leaves behind deserted islands. These technical, scientific, and environmental matters should be taken note of, and Governments should come up with rules and regulations that can keep a check on illegal sand mining. On the technological front, India is on a high rise, and a lot of development has taken come forward in remote monitoring and surveillance in the field of mining. Hence, it is fair to take advantage of the technological progression and use it to keep an effective check on mining activities, especially sand mining.

†Advocate-on-Record, Supreme Court of India. Author can be reached at naveenkraor@gmail.com.

1. Marco Hernandez, Simon Scarr and Katy Daigle, “The Messy Business of Sand Mining Explained”, Reuters Graphics (18-2-2021) <https://graphics.reuters.com/GLOBAL-ENVIRONMENT/SAND/ygdpzekyavw/>.

2. Science of the Total Environment Vol. 838, Part 1, 10-9-2022, 155877, <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155877>.

3. The South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) Report, April 2022.

4. Proloy Bagchi, “Unregulated Sand Mining Threatens Indian Rivers”, Environment, Boloji.com (14-2-2010).

5. Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957, S. 3.

6. Mineral Concession Rules, 1960, R. 70.

7. Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957, S. 15.

8. Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957, S. 23-C.

9. Press Information Bureau, Recent Initiatives of Mines Ministry to Check Illegal Mining, Press Release dated 28-3-2022. <https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1810555>.

10. Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957, S. 4.

11. Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Amendment Ordinance, 2015.

12. Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957, S. 21.

13. Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.

14. Environment Impact Assessment Notification, 2006, S.O. 1533(E) dated 14-9-2006.

15. Penal Code, 1860, Ss. 378 and 379.

16. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Sustainable Sand Mining Management Guidelines, 2016 <http://environmentclearance.nic.in/writereaddata/SandMiningManagementGuidelines2020.pdf>.

17. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate change, Enforcement & Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining (29-1-2020).

18. 2017 SCC OnLine Mad 31686.

22. Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629.

28. Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980.

29. Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974.

30. Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981.

31. Wild Life Protection Act, 1972.

33. National Green Tribunal Bar Assn. v. Virender Singh (State of Gujarat), 2019 SCC OnLine NGT 1488.

35. UN Convention on Law of the Sea,1982, Arts. 208 and 214.

36. UN Convention on Law of the Sea, 1982, Art. 194(2).

37. Convention on Biological Diversity, Art. 3.

38. Convention on Biological Diversity, Arts. 5, 6 and 7.

39. Convention on Biological Diversity, Art. 7.

40. United Nations Environment Programme, Sand and Sustainability: 10 Strategic Recommendations to Avert a Crisis, UNEP Publications, <https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/38362>.

41. Cement and Concrete Composites and Construction and Building Materials in 2006 <https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/cement-and-concrete-composites>.

42. M.C. Nataraja, P.G. Dileep Kumar, A.S. Manu, and M.C. Sanjay, “Use of Granulated Blast Furnace Slag as Fine Aggregate in Cement Mortar”, International Journal of Structural and Civil Engineering Research (May 2013), Vol. 2(2), 59-68.

43. International Journal of Sustainable Construction Engineering and Technology.

44. Chandana Sukesh, Katakam Bala Krishna, Sri Lakshmi Sai Teja and S. Kanakambara Rao, “Partial Replacement of Sand with Quarry Dust in Concrete”, International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (2013), Vol. 2(6), 254-258.

45. Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957, S. 20-A.