Bird’s-Eye View of the 5-Judge Bench Verdict on Maharashtra Political Crisis

Supreme Court: Putting an end to the Maharashtra’s Political Crisis that was witnessed by the nation after the split between Eknath Shinde and Uddhav Thackeray factions within Shiv Sena, leading to a change in the State government in the year 2022, the five Judge Constitution Bench of Dr. D.Y. Chandrachud*, CJI and M.R. Shah, Krishna Murari, Hima Kohli and P.S. Narasimha JJ., has upheld the Governor’s decision of inviting Eknath Shinde to form the Government in the State and has refused to quash Udhav Thackeray’s resignation as it was submitted voluntarily before the floor test.

Eknath Shinde Versus Uddhav Thackeray – The Fallout of Shiv Sena

In 2019, a coalition of the Shiv Sena, the Nationalist Congress Party, the Indian National Congress, and certain independent Members of the Legislative Assembly formed the government in Maharashtra with Shiv Sena’s Uddhav Thackeray as the Chief Minister. This alliance was named as Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA).

Thereafter, all 56 MLAs of the Shiv Sena issued a communication to the Speaker of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly intimating him that Eknath Shinde was appointed as the Group Leader of the Shiv Sena Legislature Party and that Sunil Prabhu was appointed as the Chief Whip of the SSLP.

The MVA continued to govern the State of Maharashtra until June 2022, when reports of some Shiv Sena MLAs meeting with leaders of the BJP started coming in. Consequently, Shiv Sena Legislature Party (SSLP) fractured into two factions: one led by the then Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray, and the other led by the Group Leader Eknath Shinde. Each faction claimed to represent the “real” political party and passed various resolutions pertaining to the affairs of the SSLP.

This marked the onset of one of the biggest political dramas, with matter reaching the Supreme Court, uddhav Thackeray resigning as Chief Minister even before the floor test and eventually, Eknath Shinde forming Government in Maharashtra by a coalition consisting of his faction of the Shiv, BJP and certain independent MLAs.

On 23-08-2022, the Supreme Court referred the matter to a five-Judge Bench under Article 145(3) of the Constitution.

Detailed Analysis of the 5-Judge Bench Verdict on Maharashtra Political Crisis

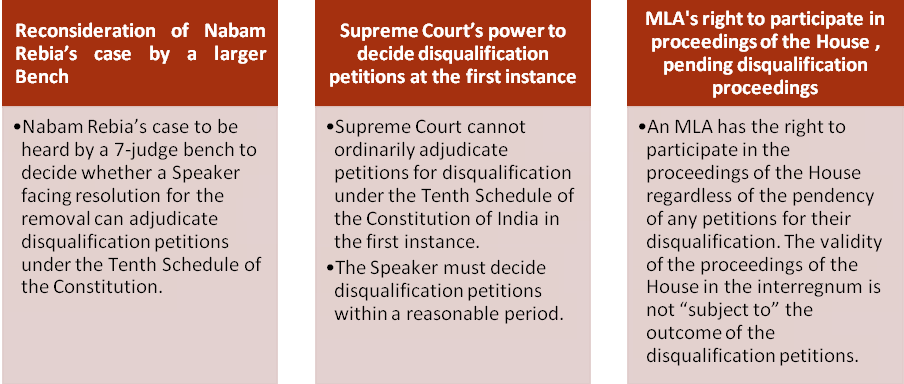

Reconsideration of Nabam Rebia’s case by a larger Bench

The Court directed the Nabam Rebia’s case to be reconsidered by a 7-judge bench because a substantial question of law remains to be settled. The Court has framed the following questions:

whether the issuance of a notice of intention to move a resolution for the removal of the Speaker restrains them from adjudicating disqualification petitions under the Tenth Schedule of the Constitution.

However, pending the decision of the larger Bench, as an interim measure, the Court laid down the following procedure to subserve the objective of the Tenth Schedule, Symbols Order as well as Article 179(c).

a. The investiture of exclusive adjudicatory jurisdiction upon the Speaker to determine the complaints under the Tenth Schedule will entitle the Speaker to rule upon and decide applications questioning their jurisdiction; and

b. (i) The Speaker is entitled to rule on applications which require them to refrain from adjudicating proceedings under the Tenth Schedule on the ground of initiation of a motion for their removal under Article 179(c). A Speaker can examine if the application is bonafide or intended only to evade adjudication;

(ii) If the Speaker believes that the motion is well founded, they may adjourn the proceedings under the Tenth Schedule till the decision for their removal is concluded. On the other hand, if they believe that the motion is not as per the procedure contemplated under the Constitution, read with the relevant rules, they are entitled to reject the plea and proceed with the hearing; and

(iii) The decision of the Speaker, either to adjourn the proceedings under the Tenth Schedule in view of the pending proceedings under Article 179(c) or to proceed with the hearing will be subject to judicial review. As the decision of the Speaker relates to their jurisdiction, the bar of a qua timet action, as contemplated in Kihoto Hollohan will not apply.

Supreme Court’s power to decide disqualification petitions at the first instance

The Court held that while it would not be appropriate for it to decide the disqualification petitions for the first time when the concerned authority had not taken a decision and that it would normally remit the matter to the Speaker or Chairman to take a proper decision in accordance with law, however, it decided to adjudicate the disqualification petitions at hand as:

(i) the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly in that case failed to decide the question of disqualification in a timebound manner;

(ii) the Speaker decided the issue of whether there was a split in the party without deciding whether the MLAs in question were disqualified; and

(iii) the necessity of an expeditious decision in view of the fact that the disqualification petitions were not decided by the Speaker for more than three years and the term of the Assembly was coming to an end.

The Court made clear that the question of disqualification ought to be adjudicated by the constitutional authority concerned, namely the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, by following the procedure prescribed.

“Disqualification of a person for being a member of the House has drastic consequences for the member concerned and by extension, for the citizens of that constituency. Therefore, any question of disqualification ought to be decided by following the procedure established by law.”

Even in cases where the Speaker decides disqualification petitions without following the procedure established by law, this Court normally remands the disqualification petitions to the Speaker. Therefore, absent exceptional circumstances, the Speaker is the appropriate authority to adjudicate petitions for disqualification under the Tenth Schedule.

Validity of the proceedings of the House in the interregnum and MLA’s right to participate in the proceedings

Article 191(2) provides that a person shall be disqualified for being a member of the Legislative Assembly if they are so disqualified under the Tenth Schedule. Article 190(3) stipulates that if an MLA incurs a disqualification under the provisions of Article 191(2) read with Tenth Schedule, their seat shall thereupon become vacant. Hence, the term ‘thereupon’ denotes that the seat becomes vacant only from such date when the Speaker decides the disqualification petition. An MLA has the right to participate in the proceedings of the House until they are disqualified.

“The decision of the Speaker does not relate back to the date when the MLA indulged in prohibitory conduct. The decision of the Speaker and the consequences of disqualification are prospective and to allow the validity of such proceedings to be subject to a future decision would lead to chaos.”

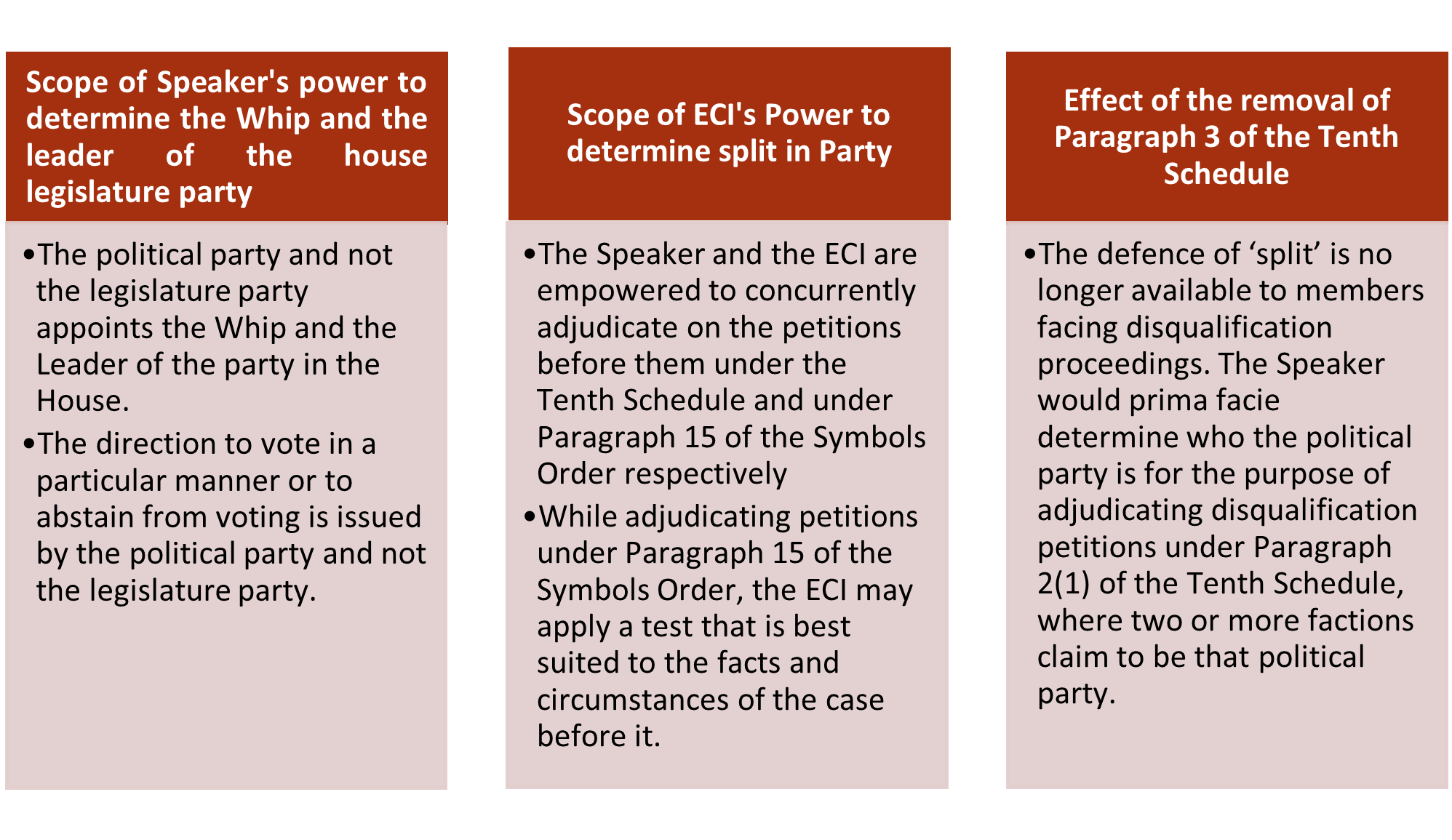

Scope of Speaker’s power to determine the Whip and the Leader of the house Legislature Party

• The plain meaning of the provisions of the Tenth Schedule, 1986 Rules, and Act of 1956 indicate that the Whip and the Leader must be appointed by the political party and not by the legislature party. Holding that a Whip be appointed by the political party is crucial for the sustenance of the Tenth Schedule, the Court explained that the entire structure of the Tenth Schedule which is built on political parties would crumble if this requirement is not complied with. It would render the provisions of the Tenth Schedule otiose and have wider ramifications for the democratic fabric of this country. Thus, the Courts cannot be excluded by Article 212 from inquiring into the validity of the action of the Speaker recognizing the Whip.

• “To hold that it is the legislature party which appoints the Whip would be to sever the figurative umbilical cord which connects a member of the House to the political party. It would mean that legislators could rely on the political party for the purpose of setting them up for election, that their campaign would be based on the strengths (and weaknesses) of the political party and its promises and policies, that they could appeal to the voters on the basis of their affiliation with the party, but that they can later disconnect themselves entirely from that very party and be able to function as a group of MLAs which no longer owes even a hint of allegiance to the political party. This is not the system of governance that is envisaged by the Constitution. In fact, the Tenth Schedule guards against precisely this outcome.”

• Further, the Speaker must recognize the Whip and the Leader who are duly authorised by the political party with reference to the provisions of the party constitution, after conducting an enquiry in this regard and in keeping with the principles discussed in this judgement.

• Consequently, the speaker’s decision dated 03-07-2022 of recognising the action of a faction of the SSLP without determining whether they represented the will of the political party acted contrary to the provisions of the Tenth Schedule, the 1986 Rules, and the Act of 1956. The decision of the Speaker recognising Mr. Shinde as the Leader, was held to be illegal.

Scope of ECI’s Power to determine split in Party until the “final adjudication” of the disqualification petitions

• The Court refused to hold that the ECI is barred from adjudicating petitions under Paragraph 15 of the Symbols Order until the “final adjudication” of the disqualification petitions under the Tenth Schedule, as it would mean, in effect, to indefinitely stay the proceedings before the ECI. This is because an order of the Speaker attains finality only after all avenues for appeal have been exhausted or are barred by the passage of time. The time that it would take for an order of the Speaker to attain finality is uncertain. T

“The ECI is a constitutionally entrenched institution which is entrusted with the function of superintendence of and control over the electoral process. The ECI, which is a constitutional authority, cannot be prevented from performing its constitutional duties for an indefinite period of time. Proceedings before one constitutional authority cannot be halted in anticipation of the decision of another constitutional authority.”

• The question as to whether the decision of the ECI under the Symbols Order must be consistent with the decision of the Speaker under the Tenth Schedule, was answered in negative as the decision of the Speaker and the decision of the ECI are each based on different considerations and are taken for different purposes.

• The decision of the ECI has prospective effect.

• The disqualification proceedings before the Speaker cannot be stayed in anticipation of the decision of the ECI. In cases where a petition under Paragraph 15 of the Symbols Order is filed after the (alleged) commission of prohibitory conduct, the decision of the ECI cannot be relied upon by the Speaker for adjudicating disqualification proceedings. If the disqualification petitions are adjudicated based on the decision of the ECI in such cases, the decision of the ECI would have retrospective effect. This would be contrary to law.

Effect of the deletion of Paragraph 3 of the Tenth Schedule

The inevitable consequence of the deletion of Paragraph 3 from the Tenth Schedule is that the defence of a split is no longer available to members who face disqualification proceedings. In cases where a split has occurred in a political party or in a legislature party, members of neither faction may validly raise the defence that they are the political party in the event that each faction files petitions for the disqualification of members of the other faction.

Members of multiple groups or factions can all continue as members of the House if the requirements of Paragraph 4(1) of the Tenth Schedule are satisfied. Two (or more) factions of a political party can both remain in the House if one of the factions has opted to merge with another political party in terms of Paragraph 4(1)(a) and the other faction has chosen not to accept the merger. However, in cases where a split has occurred, and members of one of the factions are found to have satisfied the conditions in Paragraph 2(1) and are also unable to establish any of the five defences available, they would stand disqualified.

“To hold otherwise would be to permit the entry of the defence of ‘split’ in the Tenth Schedule through the back door. This is impermissible and would render the deletion of Paragraph 3 meaningless.”

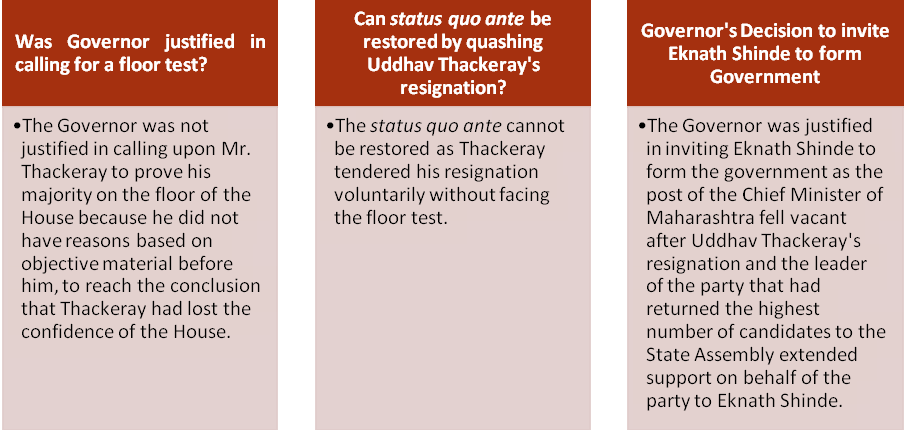

Was Governor justified in calling for a floor test?

The Governor had no objective material on the basis of which he could doubt the confidence of the incumbent government. The resolution on which the Governor relied did not contain any indication that the MLAs wished to exit from the MVA government. The communication expressing discontent on the part of some MLAs is not sufficient for the Governor to call for a floor test. The Governor ought to apply his mind to the communication (or any other material) before him to assess whether the Government seemed to have lost the confidence of the House.

Even if it is assumed that the MLAs implied that they intended to exit from the Government, they only constituted a faction of the SSLP and were at most, indicating their dissatisfaction with the course of action adopted by their political party.

“The political imbroglio in Maharashtra arose as a result of party differences within the Shiv Sena. However, the floor test cannot be used as a medium to resolve internal party disputes or intra party disputes. Dissent and disagreement within a political party must be resolved in accordance with the remedies prescribed under the party constitution, or through any other methods that the party chooses to opt for. There is a marked difference between a party not supporting a government, and individuals within a party expressing their discontent with their party leadership and functioning.”

Can status quo ante be restored by quashing Uddhav Thackeray’s resignation?

Uddhav Thackeray did not face the floor test on 30-06- 2022 and instead submitted his resignation. Hence, the Supreme Court could not quash the resignation as the same was submitted voluntarily. Had Thackeray refrained from resigning from the post of the Chief Minister, the Court could have considered the grant of the remedy of reinstating the government headed by him.

On 29-06-2022, the Supreme Court had ordered that “the outcome of the trust vote to be conducted on 30-06- 2022 “shall be subject to the final outcome” of this batch of petitions”.Since the trust vote was not held, the question of it being subject to the final outcome of these petitions does not arise.

Governor’s Decision to invite Eknath Shinde to form Government

The BJP returned one hundred and six candidates to the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly, the highest amongst all political parties, and extended its support to Eknath Shinde for the formation of the Government. Eight independent candidates also extended their support to a government helmed by Shinde.

When Shinde wrote to the Governor seeking to be called to form the Government, based on the material before him, that is, the communications received, the Governor invited Shinde to take the oath of office, and directed him to prove his majority on the floor of the House within a period of seven days.

The post of the Chief Minister of the State of Maharashtra fell vacant after the resignation of Mr. Thackeray on 29-06- 2022.

As the leader of the party that had returned the highest number of candidates to the State Assembly extended support on behalf of the party to Eknath Shinde, the Court, hence, held that the decision of the Governor dated 30-06-2022, inviting Shinde to form the Government, was justified.

[Subhash Desai v. Governor of Maharashtra, 2023 SCC OnLine SC 607, decided on 11-05-2023]

*Judgment authored by CJI Dr. DY Chandrachud

Advocates who appeared in this case :

For petitioners: Senior Advocates Kapil Sibal, Dr. Abhishek Manu Singhvi and Devadatt Kamat;

For Respondents: Senior Advocates Harish Salve, Neeraj Kishan Kaul, Mahesh Jethmalani, Maninder Singh and Siddharth Bhatnagar;

For Governor: Solicitor General Tushar Mehta.

Amazing explanation… Really fantastic